Sound In Art / Art In Sound

I wrote about the

MMAA's new Sound Art show (

Sound In Art / Art In Sound) on April 17 - just a few days after attending the exhibition opening in St. Paul. It was a great show and I felt compelled to write about every detail. So, what we've got here is a rather long feature on the exhibition, covering every piece in the show, with very little

actual detail to be found. So, for the details... you'll have to go see/hear for yourself!

A fellow sound artist suggested I do this write-up, and I've decided to just put it here at the blog. It's an excellent show and if you're anywhere near the Twin Cities, I'd highly recommend you head down to St. Paul and check it out. There's more information at the

Minnesota Museum of American Art's website.

***

Review of the Minnesota Museum of American Art’s

Auditory Exploration of the Power and Nuance of Sound:

Sound in Art / Art in Sound Remember the “Cone of Silence,” on TV’s

Get Smart? The main character, an undercover agent, would routinely meet with his Chief about something top secret and insist that their conversation be held within this giant plastic contraption which would descend from the ceiling. The “Cone of Silence,” over forty years later, inspired me when I was brainstorming how to put together an exhibit of sound art. My concept involved wall mounted buttons positioned next to information about the various sound pieces in the show, which when pushed would activate clear plastic bubbles kitted out with speakers mounted in the top, serving as single-person versions of the Cone. While you were standing beneath these plastic shields, you and you alone would be able to hear the piece.

I’m not the only person to be considering such options, these days. The problem of how to display audio art is one shared by many artists and curators as the medium of audible artwork is being embraced by more and more museums and galleries. The latest of these is the Twin Cities’ own

Minnesota Museum of American Art whose exhibition,

Sound in Art / Art in Sound, opened on Saturday, April 14, in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

A sound artist myself, I was eager to check out the show for a variety of reasons, not least of which was to see how the curators would tackle the problems of effectively presenting audio art. I also wanted to see how the artists worked to keep the interest of an audience who are more accustomed to

looking at rather than

listening to fine art.

Upon entering the exhibit, the first installation seen and then heard (

Shawn Decker’s

Green) is composed of four long, thin sheets of Plexiglas, hung separately from the museum’s high ceilings, which greet you with a carbonated series of electronic sounds. Each strip of clear plastic contains eight tiny speakers emitting a series of percussive clicks, ticks, and pops inspired by the sound patterns created by insects in midwestern meadows. Decker mimics these insects through the use of custom programmed micro-controllers, electro-magnetic sensors, and light sensors. The sounds we hear have an almost organic rhythm, changing along with small variances in electromagnetic radiation and light levels, which in turn are affected by the viewer’s presence.

Sound in Art / Art in Sound

Sound in Art / Art in Sound is largely serious in tone, with just one or two exceptions, one of which appears early on in the sequence of exhibits, perhaps to throw us off the scent.

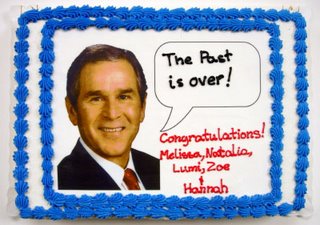

Helena Keeffe’s piece (

The Past Is Over) is funny and necessarily childish in tone, beginning from a simple idea. The artist worked with a voice impersonator and students from Oakland, California’s Rooftop Elementary School to create a series of imaginary political speeches which, if heard spoken by

G. W. Bush, would make him “the President of your dreams.” The assumption being, here, that our nation’s 43rd President has yet to give such a speech. (And it’s an assumption with which the students who worked with Keeffe on this project would seem to agree.) The most memorable faux-speech begins with, “

I am so sorry! My brain was being attacked by aliens.”

Following the silliness of Keeffe’s recordings,

Matthew Garrison’s use of sound and video recordings of military conflict seems especially fierce (

Autorange). The installation leaves an impressionistic portrait of overseas violence that is primarily composed of recordings of two large explosions that have been slowed down to create the background rumblings which form the exoskeleton of the audio portion of the piece. Within those rumbles we hear military personnel engaged in precise maneuvers, accompanied by sound effects and music. Garrison’s piece, in such close proximity to Keeffe’s lighthearted (albeit provocative) response to one of the men largely responsible for this violence, brings us back into a more serious mindset, as we remove our first set of headphones and turn our attention to the rest of the show.

Cheryl Wilgren Clyne

Cheryl Wilgren Clyne’s

Three features recordings of the artist’s granddaughter as she improvises and experiments with her newfound abilities in the realm of speech. Video, featuring sepia toned moving images of children and bicycles projected onto a large screen in the entry to the main gallery space, was added later in an attempt to focus the direction of the sound. The audible portion of the installation is amplified from two small speakers resting on top of the video projector, positioned high above our heads. Clyne’s decision to amplify the soundtrack with speakers, rather than utilizing sets of headphones (as does every other sound and video artist in the show) is quite daring, especially considering the noise levels at Saturday’s opening reception.

Moving on, we find ourselves confronted by two listening stations, with two sets of accompanying headphones. Distracted by movement from the left, however, I remind myself to head back that way and approach a large metal frame serving as support for a giant, moving band of metal which is making inviting sounds. An endlessly undulating loop, this doesn’t grate the way the repetition of a recorded loop can, as it changes in subtle and dynamic ways, never truly repeating itself vibration for sonic vibration.

This piece (

Jack F. X. Pavlik’s

The Storm) has long been a favorite local sculpture, although I hadn’t previously considered the aural component as closely as I was encouraged to on this occasion. The kinetic sculptor incorporates a small, virtually silent motor, which quietly manipulates a long, rigidly flexible piece of sheet metal to create two events: a languid, wave-like shape which sways tirelessly and hypnotically; and the accompanying sound, as you might imagine would result from the movement of a very long strip of metal, flexing and vibrating in a slow, unending loop. What you hear is perhaps reminiscent of sounds from outer space, something heard underwater, or the imagined sound of radio transmissions from a stranger’s dreams. The sculpture is both beautiful to see and to hear.

Before heading back to the two listening stations, I stop to inspect an assemblage of wood, glass, and rubber hose, which turns out to be a kind of science experiment conducted by sound sculptor,

Leif Brush, made in an effort to record a very specific sound in nature. The artist likes to record “normally undetectable natural sound phenomenon” like the sound of a tree growing, or perhaps the trickle of water as it moves through the soil deep underground. Leif Brush was one of the first artists to embrace sound as a legitimate artistic medium, beginning in the 1970s when he used his knowledge of earth science and electronics to earn an MFA in Audible Sculpture from the School Of The Art Institute of Chicago. He’s currently working with satellites, global positioning technology and cellular phones to create “sound weavings.”

Along with Shawn Decker’s micro-controllers and electromagnetic sensors, this particular part of the show would fit as comfortably within an exhibition at the Science Museum as it does here at the MMAA. One absolutely comes away with the impression that the science involved is as much a part of this work as the sound, and it is fascinating; but it also has the effect of distracting from the presentation of the audio.

The Frost Printer by Leif Brush, along with photographs by Gloria DeFilipps Brush, presents the account of the recording of the activity of frost formation. Warm water trickles down a tube attached to a barn sash window, outfitted with sound sensors, at ten degrees below zero. (

Leif Brush is from Duluth, MN by the way – sounds like a Duluth winter, to me.) The warm water instantly forms layers of frost on the panes of glass, creating “sub-audio sounds” which are picked up and recorded by the attached sensors. Unfortunately, the sounds were so “sub” that they were lost in the vastness of the room. I couldn’t find headphones, and the audio was nowhere to be heard, otherwise.

In an exhibit full of work by sound artists, the problem of how to effectively keep the pieces from overlapping on top of each other (becoming, in effect, a

collage of sound art) is perhaps the primary cause for concern. I didn’t have a chance to talk with curator Theresa Downing, though I imagine she would agree that visual art curators don’t have this particular kind of problem (at least not to the same extent). When visual artworks compete with each other for attention, the solution may simply be to move one work a bit further from its neighbor, out of the line of sight. With sound, however, you must isolate the individual pieces in such a way that they are less capable of infringing on the audible space of their fellow presenters. This is a much more difficult task.

At the opening of

Sound in Art / Art in Sound, the problem of hearing the pieces was exacerbated by the noise coming from the large crowd of appreciative viewers (

listeners?) and also from a (wonderful) performance by Minneapolis-based sound art duo,

Beatrix*JAR. The duo’s performance was rhythmic, funky, and surreal, but it also made the problem of effectively presenting sound art come dramatically into focus.

For instance, if I hadn’t gone back the next day to try and pick out some of what I’d missed, I’d be completely unable to convey the humor of

Abinadi Meza’s

Creature. The piece seems to consist of a collage of sounds made by a small cat, recorded while confined within the bag which now contains the speakers which amplify that sound recording. The bag is a modern pet carrier, much softer than a cage, but the imprisoned cat is recorded pawing and scraping, mewing and groaning in much the way my own cat does whenever I’m forced to confine him in a large cardboard box (punched with dozens of air holes, of course) for car rides to the vet. I was only able to really listen to the piece by going back to the show the next day, and even then I had to get down on my hands and knees, pressing my ear closer to the bag, to hear it. I’d have listened longer, but my knees began to ache (

and I think I may have given the museum’s security guard some cause for concern kneeling on the floor, dangerously close to one of the museum’s artworks)!

I’m afraid sound art shows are doomed to rooms full of headphones for this reason, as the pieces which were least likely to be in constant competition with the other sounds in the room (which admittedly is occasionally the artist’s intent) were the ones which offered a set of private earphones, aiming the audio directly at our eardrums.

Another of Abinadi Meza’s pieces,

Beacon (also presented in headphones), seemed to intersect with Pavlik’s steel waves and Brush’s frost recordings, as it documented the sounds of snowflakes hitting a steel plate on a winter evening in Minnesota. The inclusion of the sound of snowplows overwhelms the sound of snowflakes, just as the actual plows were overwhelming the piles of flakes at the time of the recording. The addition of video material served that extra purpose of keeping the interest of those of us who have been trained to walk through a museum relatively quickly, observing each piece only briefly before moving on, but rarely as long as the duration of many of these audio works. The inclusion of visual stimulation no doubt encourages the patron to listen longer to the driving force behind the piece.

Mike Hallenbeck was one of two artists to present his audio art

à la carte, an approach I, personally, favor.

Sound Spandrell is an “acoustic architectural portrait of the ‘silent’ gallery space” at the MMAA, consisting of a collage of “incidental and idiosyncratic sounds” one might not otherwise have paid attention to while standing alone in the empty room. This piece was intriguing for many reasons, not least of which was the effect it had on my perception of other “non-art” sounds in the gallery. Not unlike Cage’s composition,

4:33 (which in contrast to most musical compositions, including Hallenbeck’s, is in fact “silent”), the piece has the effect of making the listener much more aware of the sounds already in the room. Were my fellow art patron’s squeaking tennis shoes an impromptu addition to the work? What about the contribution of the front doors, faintly heard opening and closing at odd intervals during the course of the run of the piece?

Anne Wallace, whose listening station was mounted right next to Hallenbeck’s, similarly presents her sound collage composed of sounds found in and around the Clear Fork Watershed of the Brazos River, including the rhythmic chanting of birds. Whether it was a trick of production or something naturally present at the site of recording, the result is quite soothing, especially after so much audio intake. Winged creatures given credit on this recording include mockingbirds, geese, owls, hens, wild turkeys, woodpeckers, kingfishers, ducks and jet planes.

Perhaps the most ambitious project in the show is

Urban Echo by

J. Anthony Allen and

Christopher Baker (another piece offered through headphones and accompanied by video projected against the gallery walls). The piece combines sounds recorded live from four locations around the Twin Cities, ambient sounds recorded live in the gallery, and individual contributions from participants’ cellular phones. Patrons are invited to leave voicemail and text messages answering the questions: “

What do you hear? What do you want others to hear?” The voicemail recordings float throughout the piece, and the text messages pop up beneath a video projection consisting entirely of a constantly changing, moving map of the Twin Cities area, as the location of each text messenger is pinpointed (thanks to the inclusion of a zip code in their message). The result is a dizzying awareness of the size of the area and the far reaches from which the show’s many viewers have traveled. The artists seem to be as interested in exploring interactivity in art as they are in technology and audio art.

All in all, this is a groundbreaking show for the Twin Cities and a fascinating exploration of sound art. Jack F. X. Pavlik’s kinetic sculpture and Allen and Baker’s map were standouts for me, as were the 32 tiny speakers mimicking the sounds of nature, presented by Shawn Decker. And while curators didn’t use anything like my “Cone of Silence” concept, I did find a good variety of both familiar and unfamiliar methods for presenting sound art. You may be surprised to experience a heightened sense of sound awareness, upon leaving the exhibition. If one indication of a successfully communicated piece of art is the work’s ability to create that kind of change in perception, then I would call this show a resounding success!

The exhibition runs through July 1st, 2007 at the

Minnesota Museum of American Art, which is located at 50 West Kellogg Boulevard in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

You can find more information about the show at the

MMAA website.

Junkshop Coyote is Mitch Hilton, from Indianapolis, Indiana. He runs a net label called Hallo Excentrico! and produces elecronica/collage, citing Aphex Twin and V/Vm as major influences.

Junkshop Coyote is Mitch Hilton, from Indianapolis, Indiana. He runs a net label called Hallo Excentrico! and produces elecronica/collage, citing Aphex Twin and V/Vm as major influences.